Sargent and the Burckhardts

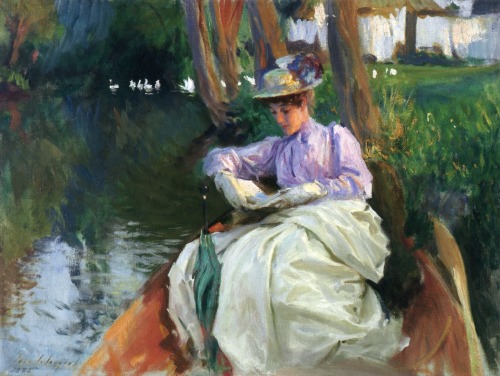

Valerie Burckhardt, 1878

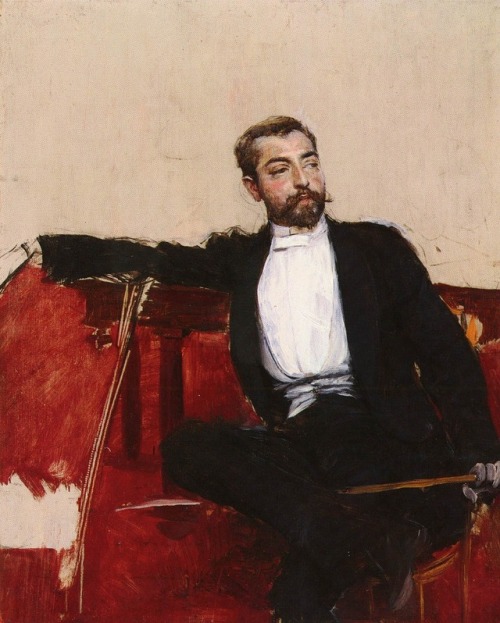

Edward Burckhardt, 1880

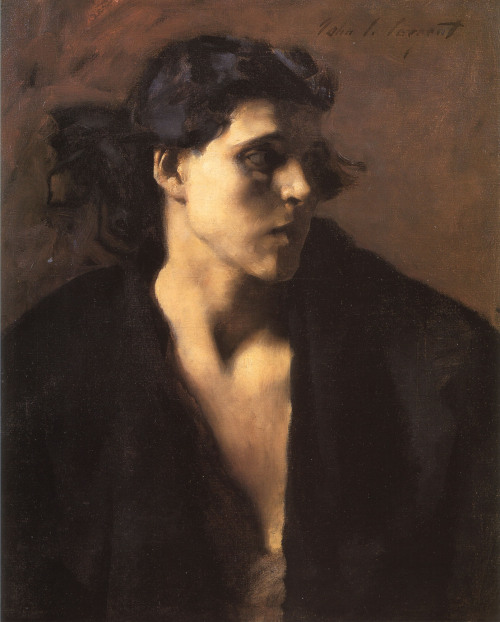

Lady with a Rose (Charlotte Louise Burckhardt), 1882

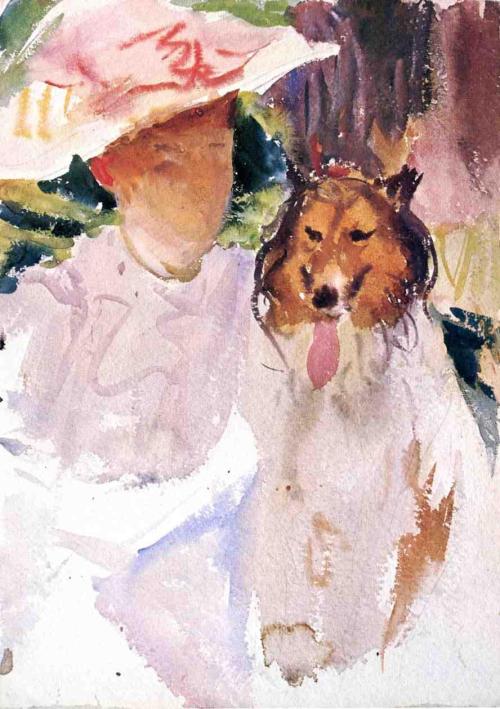

Pointy (Portrait of Louise Burckhardt’s dog), 1885

Mrs. Edward Burckhardt and Her Daughter Louise, 1885

Edward Burckhardt was a well-to-do Swiss merchant; his wife, Mary Elizabeth Burckhardt (née Comes) was American. John Singer Sargent’s parents, expatriate Americans who travelled the European circuit, apparently socialized with the Burckhardts, such that their children knew each other growing up. Sargent was friends with Valerie, the older of the two Burckhardt daughters, and painted her portrait in 1878 while he was still a student in Paris. Valerie would have been about 21 at the time, a year younger than Sargent.

According to some accounts they may have been romantically involved, but if so it didn’t come to anything; two years later, in 1881, Valerie married a Swiss silk merchant named Harold Farquhar Hadden. Sargent presented her with a portrait of her father as a wedding gift.

During 1881 and 1882, Mrs. Burckhardt tried to create a match between Sargent and her younger daughter, Charlotte Louise (who went by her middle name). Louise was 19, Sargent 25. According to Deborah Davis’ book Strapless:

People who knew Louise described her as a pleasant but unremarkable young woman. Some acquaintances even suggested she was a little stupid. Above all, she was a docile and obedient daughter, dedicated to fulfilling her mother’s ambitions for her.

According to Davis, Mrs. Burckhardt actively plotted to bring the two together.

She invited Sargent and his friend James Beckwith to Fontainebleau and other nearby destinations that would remove them from the distractions of Paris. Normally, Sargent seemed to have no time for romance… But this summer was different… He appeared to warm to Louise and actually welcomed opportunities to be alone with her. Beckwith caught them unaccompanied several times — something that would never have happened during those days of constant chaperones if Mrs. Burckhardt had not counted on a wedding in Louise’s immediate future.

Inexplicably, however, Sargent’s interest waned and evaporated completely by the end of the summer. At the very moment when Mrs. Burckhardt felt closest to attaining the prize of a marriage proposal for Louise, the artist baffled her by reverting to his friendly, yet decidedly platonic, relationship with her daughter. Louise confronted him at his studio, hoping for an explanation. Sargent had the difficult task of convincing her that their flirtation, if it could be called that, was over. Their unpleasant conversation was interrupted by Beckwith, who walked in on them and saw that there was “evidence of trouble.” Sargent confessed to him that although he valued her friendship, he didn’t care for Louise in a romantic way.

I wonder what the “evidence of trouble” was. In my imagination, Louise had been visibly crying.

It’s not clear when exactly Sargent began his large, full-length portrait of her, though his work on the painting spanned the time when their on-again, off-again romance was playing out.

The painting came to be called Lady with a Rose.

The amazing thing for me about Sargent’s portraits is the way they communicate their subjects’ humanity. It’s not just a likeness. It’s a person, captured in a particular moment that tells a story. Photography may have replaced painted portraits, but I doubt even a skilled photographer could do what Sargent did, sitting with a subject for hours, even days; conversing, taking breaks at the piano, trying different approaches, and finally choosing one particular moment to commit to canvas.

And Sargent was honest, sometimes brutally so. His realism has gone in and out of fashion, his technique sometimes lauded, sometimes criticized, but his honesty endures.

When I look at Lady with a Rose, I see Louise posing dutifully with one hand on her hip and the other holding up the rose, but her expression has a hint of exasperation. Really, John? I have to hold it like this for how long? Her head tilts a bit, but her gaze is steady, if a bit resigned. And I wonder: Is Sargent depicting the moment in which she finally reconciled herself to the fact that the relationship between them wasn’t going to happen? That this painting of her, with the heavy black dress and the slightly silly pose, chosen by Sargent to echo the Spanish master Velasquez, was all she would be left with for the summer spent with the handsome artist, the friend of her older sister whom she may have spent years quietly admiring?

Sargent entered the painting in the 1882 Paris Salon, and it immediately created a buzz. The young artist’s virtuosic technique, along with the intriguing expression of his subject, captivated viewers. Lady with a Rose made Sargent’s reputation. Along with the other painting he exhibited that year, a dramatic depiction of a Spanish dancer called El Jaleo, it put him in the first rank. Commissions began coming in. Novelist Henry James wrote of the young Sargent that he offered “the slightly ‘uncanny’ spectacle of a talent which on the very threshold of its career has nothing more to learn.”

Three years later Sargent’s fortunes had turned. The scandal that followed the exhibition of Madame X at the 1885 Salon caused his commissions to evaporate. Sargent was in financial difficulty, and reportedly was considering giving up painting altogether. It may have been as a favor to him that his old family friends, the Burckhardts, commissioned a new painting.

First, though, Sargent painted and gave to Louise a painting of her dog, Pointy. I wonder if the white around the muzzle is an indication of Pointy’s age. The name seems like the kind of name a young child would give; Louise was 23 in 1985, but maybe Pointy’s name dated back to a time when she would have given such a name to a pet. And I wonder, too, if the gift was in a small way meant to make amends for what she had been through in 1881-82.

The painting the Burckhardts commissioned was a dual potrait of Louise and her mother. Mrs. Edward Burckhardt and Her Daughter Louise fascinates me. Louise is relegated to the background. At least she gets a more-comfortable pose this time, with her arms resting on the back of her mother’s chair. She still gazes directly at Sargent, but there’s a distance there that wasn’t there in Lady with a Rose. She looks almost startled, or at least somewhat taken aback. In my mind, posing for Sargent has brought her back to an emotional place she would have preferred not to revisit.

Maybe the distance isn’t all on Louise’s side. Maybe Sargent doesn’t want to revisit her face, doesn’t want to repeat himself, to risk falling short of the standard he set in recording the enigmatic expression that so captivated the critics previously. Or maybe he was rushing the depiction of Louise in order to concentrate on the picture’s real focus: her mother.

Mrs. Burckhardt sits for the portrait, but can’t bring herself to look at the artist. She gazes off to the side, outwardly composed, but with the tension visible in the left hand clutching the arm of the chair. And taking the two sitters together, mother and daughter, the story gets stronger: The thwarted matriarch, forced to endure the young man who was the author of her failure, looking away from him and even more, from her daughter, the one who actually suffered most in all this.

I keep coming back to Mrs. Burckhardt’s face, her look of memory and regret.

Four years later Charlotte did marry: an Englishman, Alfred Roger Ackerley. She fell ill with tuberculosis just two years later, though, and died at the age of 30.

Her older sister Valerie outlived them all. She had moved with her husband to New York, and sometime around 1922 she wrote to Sargent, including a photograph of the dual portrait of her mother and Charlotte, but with Charlotte blotted out. Apparently she wanted to know if Sargent would paint over her sister, making the painting a solo portrait of her mother.

Sargent’s reply:

I will return the photographs to you – as I found the composition as a whole is destroyed by taking out such an important part of it and leaving a gap instead. I cannot consent to do that any more than I would wear my hat in a drawing room or eat peas with a knife at dinner.

I wish you would send me a photograph of the picture as it is without the figure of Louise having been taken out. I would know better if anything can be done about it, and also what is wrong.

I know it’s unfair to try to draw a curve through two points, but looking at Louise’s portrait, and then thinking about her desire to have Sargent paint over the image of her dead sister, she doesn’t come across as a very nice person.

Reposted from http://ift.tt/1hp1dqa.