Mrs. George Batten (Mabel Veronica Hatch), ca. 1897 I was…

Monday, September 23rd, 2013

Mrs. George Batten (Mabel Veronica Hatch), ca. 1897

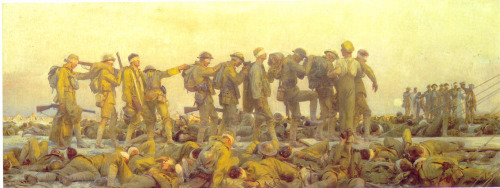

I was browsing through the Sargent paintings at wikipaintings.org, looking at all the commissioned portraits, and thinking how they tend to follow a certain pattern: Attractive young woman (frequently, an American heiress married to European nobility to save the estate à la Downton Abbey), standing in an awesome dress while staring boldly at the viewer. And then I came across this one, and thought: Whoa. That’s different. Did some wealthy woman actually choose to be painted having an orgasm?

The wikipaintings page doesn’t tell much about the work, other than the name of the subject. But the jsgallery.org page for the painting has a more descriptive title, and some awesome details:

Mrs George Batten Singing

John Singer Sargent — American painter

c. 1897

Glasgow Museums: Art Gallery and Museum, Kelvingrove

Oil on Canvas

Signed and Inscribed across upper edge: To Mrs. Batten John S. Sargent

Mrs. Batten (nee Mabel Veronica Hatch, c. 1857-1915) was the daughter of an upper-class military family, and grew up for a time in India. There she met and married George Batten, an older military officer, and later they moved to London. In 1908 she began a lesbian affair with the author Marguerite Radclyffe Hall. She was a talented amateur mezzo-soprano. Sargent admired her and presented her with this portrait.

Ah. The portrait wasn’t a commission, but something Sargent was inspired to paint on his own. And she’s singing. But maybe I can be forgiven for missing that on my first viewing, since Sargent has so beautifully captured a moment of (musical) passion that is at least ambiguous in tone. And I have to think it not an accident that he chose to celebrate her being carried away by the emotion of the piece she was singing, just as she apparently was carried away by a romance that I assume caused a stir among her Victorian contemporaries.

Reposted from http://lies.tumblr.com/post/62110750815.