alwaysalliemae:

I don’t understand why netflix keeps buffering.

It’s almost like it doesn’t want me to spend all day watching this show.

This is something I’ve (unfortunately) learned more about lately, so I thought I’d share. Note that I don’t know that this applies to your particular situation. But if you’ve investigated and found out that your Internet connection is generally fast to other sites, but slow when streaming videos from Netflix and/or YouTube, this may be affecting you.

Adding a cut because it got kind of long.

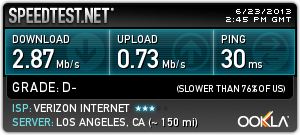

My home Internet access is via Verizon DSL. I’m generally happy with it. It’s not a particularly fast connection by modern standards, but it’s good enough for me. Here’s the output of a speedtest.net test I just ran:

During a year-long obsession with the Lizzie Bennet Diaries (if you follow me you definitely don’t need me to tell you that), I became quite familiar with my connection’s YouTube-streaming capabilities. With nothing else consuming my downstream bandwidth, I could reliably stream from YouTube at 720p with only the occasional brief pause to buffer, and if I was willing to wait a few minutes I could spool up an entire 5-minute video at 1080p.

A few months ago, though, I started noticing a sharp drop in my YouTube performance. It came and went, but when the problem was there I was unable to stream at 720p, or even at 480p or sometimes even at 240p, without long waits for buffering.

Some investigation showed the following:

- It was not due to something else using my local network, because it persisted even when I turned off my wifi and disconnected all other devices besides my desktop computer.

- It was not due to something else running on my computer, because I could use the ‘ps’ and ‘top’ utilities to inspect what was running in the background.

- The problem appeared to be specific to YouTube. Speedtest.net, as well as random browsing, showed that my download speed from other sites was fine, even while YouTube remained slow.

- It seemed to get worse during peak hours (daytime and evening). It was usually fine in the early morning or late at night.

Things got worse over a period of weeks, until YouTube was essentially un-streamable for me for much of the day.

Pause to explain something: I have a few good friends, and a larger circle of acquaintances, who are really good at network engineering. These are the people who basically taught me most of what I know about the Internet and Unix computing, and to whom I owe my career as a programmer and Internet developer. The group includes a number of current and former employees of major Internet companies, including some senior people in Google’s SRE and testing operations.

I asked them what was going on. Disclaimer: I’m not a network engineer myself, and may be a little confused about some of this. But the explanation makes sense in terms of what I’m seeing at my end.

This is a known issue inside Google. Users at certain large ISPs had begun complaining about slow YouTube connections a number of months ago, but investigations by Google showed that the problem was not at Google’s end. Instead, it was the result of poor network performance at the point where the users’ ISPs connected to the major Internet backbone providers, specifically to the content data networks (CDNs) that distribute YouTube content.

The Google investigators’ conclusion, as passed to me, was carefully worded: They had not found any cases of deliberate “throttling”, in which the ISP was directly and intentionally degrading users’ access to video content from popular video-streaming sites. What did appear to be happening, though, was that the ISPs were intentionally failing to upgrade their capacity in the part of their network that handled their users’ growing video-streaming traffic.

As I dug into it more I found some good articles by Stacey Higginbotham and Om Malik at GigaOm that explain what’s going on:

An older article by Higginbotham gives additional background:

Summarizing: Some major ISPs, in particular Time Warner Cable and Verizon (though possibly others) are deliberately letting their customers’ Internet performance degrade when it comes to streaming video from popular sites like Netflix and YouTube. They have been doing this by failing to maintain adequate data capacity to the Internet backbone, specifically for connections to the CDNs that carry the sites’ video traffic.

Why would ISPs choose to do that? In the case of Time Warner Cable, I assume it’s at least partly about the inherent conflict of interest between helping customers get their video from the Internet while also charging them for a TWC cable subscription. Pressed by angry customers for an explanation of what’s going on, Jeff Simmermon wrote a post on the TWC company blog on June 13: Explained: Why Internet Traffic Slows At Times. It’s a lot of hand-waving and denial of outright throttling, but it never really addresses the issue. Instead, it offers a bunch of vague generalities about how the Internet works. My interpretation: Complete bullshit.

With Verizon it’s a little trickier. They don’t have the same conflict of interest that TWC has, since they aren’t also selling their customers access to non-Internet video. But they still want to maximize their own revenue. As far as I can tell, what Verizon is trying to do is what I would call “double dipping.” They’re trying to charge for the bits they’re delivering twice: Once when the customer pays them for a DSL or FIOS connection. And then again, by making the companies that provide online video content (Google/YouTube and Netflix, and the CDNs that deliver that content), pay Verizon for access to their customers. Verizon is intentionally letting their customers’ video-streaming quality degrade, because by doing so they can put pressure on Cogent, the CDN from whom Verizon gets most YouTube content, to pay Verizon a fee every time Verizon has to add more video-carrying capacity.

The technical term for the agreements under which major Internet backbone providers and ISPs connect to each other is “peering.” On June 19, David Young of Verizon posted the following on the Verizon Policy Blog: Unbalanced Peering, and the Real Story Behind the Verizon/Cogent Dispute. This is a much-more specific and substantive response to the issue than Simmermon’s blog post for TWC. Young writes:

The authors [of the GigaOm article I linked to above] accurately describe settlement-free peering as “essentially an arrangement between two bandwidth providers where they send and receive traffic from each other for free.” It goes on to say: “the logic is that the data sent from one network to another is reciprocated.”

What the article doesn’t say, however, is that Cogent is not compliant with one of the basic and long-standing requirements for most settlement-free peering arrangements: that traffic between the providers be roughly in balance. When the traffic loads are not symmetric, the provider with the heavier load typically pays the other for transit (see our ex parte filing [PDF] from the 2010 Comcast/Level 3 spat for more info on peering and transit agreements). This isn’t a story about Netflix, or about Verizon “letting” anybody’s traffic deteriorate. This is a fairly boring story about a bandwidth provider that is unhappy that they are out of balance and will have to make alternative arrangements for capacity enhancements, just like any other interconnecting ISP.

Here again, as a customer paying Verizon for Internet access, and as a person who’s been involved with building and using the Internet since the 1980s, I call bullshit. I’m sure Verizon would like it if there were a tradition that peering arrangements on the Internet be balanced in the way he describes. I don’t doubt that they make a case that such a standard exists in their comments on the Comcast/Level 3 lawsuit. But such a standard does not, in fact, exist. In fact, such a standard would be fundamentally inconsistent with the most basic design principle of the Internet.

This gets talked about under terms like “Net neutrality”, but most Internet users don’t really understand what that means. What it means is, the Interent from its earliest days has been designed to be “dumb in the middle.” Unlike the early phone networks with which it competed (and which it has now largely replaced), the Internet is designed to be a neutral platform through which data flows in an unrestricted fashion, with the intelligence for which data goes where residing not in a centralized switching apparatus, but on the edges of the network, on the client the makes a request and the server that satisfies it. On the endpoints, rather than in the middle.

There’s no fundamental law of nature that says you have to build a network this way. There’s no God-given commandment that the Internet backbone providers have to cooperate with each other to maintain a system that is, in essence, a level playing field in which all the data sloshes around more or less agnostically. You don’t have to build it that way. But that’s how the Internet was actually built, and that’s why it succeeded. Verizon would like for the Internet to work more like the old phone system, because that would give big players like Verizon more control, more opportunity to pressure smaller players to pay Verizon on terms advantageous to Verizon. But that network would not be the Internet. And it would suck for its users, in the same way that the old-style telecom system and the old-style cable networks and the old-style standalone online services sucked for their users: Because they were closed systems with central gatekeepers, and you got only what the gatekeepers chose to give you.

The Internet broke that model, opening up the network to anyone who had bits to offer, and because the network was designed to carry those bits reliably and quickly without regard to where they came from and where they were going, things like the Web were born, and then blogs, and YouTube, and Tumblr, and everything else awesome about the Internet.

Sorry. I guess I just have a lot of feels about the Internet, as you kids would say. Calming down now.

It’s not that the Internet is a hippy-dippy paradise where all this should happen for free. But when the profit motives of the companies that run the central part of the Internet are in conflict with the Internet’s inherent design principle, the design principle has to win or the Internet stops being the Internet. That’s what Verizon is trying to do here, and as part of that they’re making misleading arguments about a mythical tradition of balanced peering. They’re making false claims of not intentionally letting their customers’ experience deteriorate, when that is, in fact, exactly what they’re doing.

That blog post of Young’s on the Verizon Policy Blog has a form for adding comments at the bottom. “Join the Discussion” it says. It’s funny to me that in the four days that post has been up there apparently have been no comments deemed worthy of approval by the moderator. It’s kind of hard to have a discussion when you’re the only one talking.

Hopefully Verizon’s customers will figure out what’s going on, and will complain about it. If enough people make enough noise, maybe Verizon will have to stop treating them like sacrificial pawns. If enough people start switching to other providers (assuming real competition for Internet providers is allowed to exist), Verizon will have an incentive to do the right thing.

In the meantime, in the best tradition of the Internet, I’m treating Verizon’s actions as damage and routing around it. By setting up a VPN to a machine I maintain in another part of the Internet, I can stream YouTube traffic without going through Verizon’s overloaded Cogent connection. It works pretty well; there’s a slight drop in performance to non-YouTube sites, but YouTube is pretty important to me these days, so I don’t mind. Another approach you might look into if you’re experiencing this is to use a proxy setup to browse to YouTube (or Netflix) via a different host somewhere else on the net, not behind your current ISP.

These sorts of workarounds defeat the purpose of CDNs and make the overall Internet less efficient at moving bits around, which brings me back to why Verizon’s actions in this case make me sad.

Oh well.

Aren’t you glad you asked why Netflix keeps buffering? :-)

tl;dr: Verizon and Time Warner Cable (maybe others?) are intentionally letting their customers’ streaming of YouTube and Netflix videos degrade. They hope you won’t notice. There are things you can do about it, but they’re kind of complicated.

Reposted from http://lies.tumblr.com/post/53688927303.