National Birthdays, Real and Imagined

It’s hard to escape the topic of nation-birthing these days. For example, there was that only-slightly-premature delivery of the new Iraqi state. I haven’t felt like saying much about that, though I did very much like GYWO #37, which featured the following:

Nothing says “Good luck” like handing off sovereignty and then running straight to the airport. Do we always treat sovereignty like it’s a goddamn grenade?

I thought that was pretty funny, but it’s one of those “funny because it’s true” things. Transfers of sovereignty are exactly like a grenade, as pretty much anyone who’s read history knows.

I’ve been reading more history lately. I think I needed an emotional break from the raw news of the day. It’s comforting, in a way, to look back on a political debate with the benefit of centuries of hindsight. Things are more certain in the past. People disagree with each other, they yell and fume and make scurrilous charges against their opponents, but as an observer I’m comfortably insulated from their fears and uncertainties. For me, it’s already over. I know how it turns out.

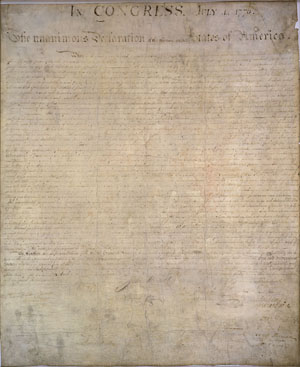

Currently I’m reading a book I’ve been wanting to read for a while, but have never gotten around to before now. It’s David McCullough’s John Adams, and as I lay in bed tonight I read the part where McCullough describes the debates in Philadelphia in the spring and summer of 1776 that led to the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

It’s a great story. The tension builds; the delegates scrabble back and forth like football players chewing up the same turf over and over, but the ball is moving inexorably toward one end of the field, toward a formal break with England, and they all know it.

On July 1 John Adams delivers the speech of his lifetime, making the case for independence with relentless logic, pounding his opponents like a single-minded fullback; no fancy reverses or trick plays, just power drives up the middle.

But stopping him on the 1-yard line is the Pennsylvania delegation, unwilling, in their Quaker pacifism, to take the final, irrevocable step of voting in favor of a declaration that they know will mean years of bloody war. Exhausted, the delegates agree to put off the vote to the following day.

The atmosphere that night at City Tavern and in the lodging houses of the delegates was extremely tense. The crux of the matter was the Pennsylvania delegation, for in the preliminary vote three of the seven Pennsylvania delegates had gone against John Dickinson and declared in the affirmative, and it was of utmost interest that one of the three, along with [Benjamin] Franklin and John Morton, was James Wilson, who, though a friend and ally of Dickinson, had switched sides to vote for independence. The question now was how many of the rest who were in league with Dickinson would on the morrow continue, in Adams’s words, to “vote point blank against the known and declared sense of their contituents.”

To compound the tension that night, word reached Philadelphia of the sighting off New York of a hundred British ships, the first arrivals of a fleet that would number over four hundred.

The next morning, Caesar Rodney, a pro-independence delegate who had been absent the day before, arrived just as the doors to the Continental Congress were about to close, having ridden 80 miles through the night so he could cast his vote and break the 1-1 tie of his Delaware delegation.

Yet more important even than the arrival of Rodney were two empty chairs among the Pennsylvania delegation. Refusing to vote for independence but understanding the need for Congress to speak with one voice, John Dickinson and Robert Morris had voluntarily absented themselves from the proceedings, thus swinging Pennsylvania behind independence by a vote of three to two. What private agreements had been made the night before, if any, who or how many had come to the State House that morning knowing what was afoot, no one recorded.

The birth of our nation arguably didn’t come later that day, when each of the colonial delegations (except for New York, which abstained) voted in favor of independence. And it certainly didn’t come two days later, on July 4, when they finally got all the paperwork drawn up.

If there was a moment when our country really was born, it was late that night, the night of July 1, or perhaps in the wee hours of July 2, 228 years ago this very night, in a smoky Philadelphia tavern, or maybe in a quiet lodging room, as the two sides faced up to the realities of their situation and the opponents of the Declaration agreed to stand down.

Here’s a toast to back-room deals, and real anniversaries, and impassioned partisans willing to step back from their bickering and make common cause, pledging their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, even in the face of a future that, for them, was still very much in doubt.

July 2nd, 2004 at 6:58 am

I have had a real issue with cynicism lately. All of this war = patriotism = GOP. I have gotten so turned off by the Conservatives attempt to steal the flag that I have to remind myself on occasion that this is still my country. Thanks for helping me remember what this weekend is about… A bunch of rich, white, slave owners who didn’t want to pay their taxes.

July 2nd, 2004 at 9:20 am

You’re right Thomas – you apparently do have an issue with cynicism! Hopefully, it was mixed with some good-natured sarcasm in this case!

I’ve been trying to read the very same book lately. Well-stated post, John!

July 2nd, 2004 at 9:28 am

Thank you for this post. though I have my own cynicism reserves, at heart I’m also an idealist, plus i used to live a few blocks from Independence Hall, so I used to think about those guys a lot as I walked through that neighborhood. I love this story, and I work toward its spirit as much as I can. I’ve also been wanting to read that book but haven’t gotten around to buying it yet. (If you don’t want to keep your copy, if it IS yours and not the library’s, I’ll take it off your hands when you’re done at some price to be named later.)

July 2nd, 2004 at 8:48 pm

Nice post.

Backroom deals are always fun until some gets the bill. And usually, it’s the people who weren’t in the backroom that pay it.

But your right. In this case and many others, the deal can work for the greater good. They’re just really hard to predict or ‘regulate’.